Tradition meets Contemporary essay

This essay was written for an exhibition organized by Rossi & Rossi (London) for Asia Week (NYC, March 2008). All images are copyrighted to gallery (antiques) and Jason Sangster and the artists (contemporary) . As usual, this is intended for friends and family and not for reproduction.

This essay was written for an exhibition organized by Rossi & Rossi (London) for Asia Week (NYC, March 2008). All images are copyrighted to gallery (antiques) and Jason Sangster and the artists (contemporary) . As usual, this is intended for friends and family and not for reproduction.I cannot figure out how to post more images here, so the collection of 17 contemporary and 5 traditional images I reference are available as a gallery at http://picassaweb.google.com/leigh.sangster

Meeting Old Buddhas in New Clothes

Leigh Miller Sangster[1]

In the exhibition Tibetan Encounters: Contemporary meets Tradition centuries of Buddhist iconography and cosmological forces are re-envisioned as they are mapped onto the twenty-first century. This challenging exercise was borne of the Rossi & Rossi commission of seventeen of the best contemporary Tibetan artists to respond to a set of Tibetan Buddhist arts from the 13th - 18th centuries. Although they are presently working within and outside of Tibet, almost all of the artists have experienced the world of traditional Buddhist arts in monasteries, a quintessential component of the Tibetan cultural landscape. Yet this collaboration between the past and present is unique. Rather than a part of their collective acculturation, or the requisite subjects of study in the course of their art school training, the engagement here is of mature artists interrogating the relationship of their own techniques and world views with that of their artistic and cultural heritage.

I.

In asking what continuities we, and contemporary artists, see with the arts of pre-twentieth century Tibetan Buddhist tradition, we are asking how that tradition becomes situated or is located within the 21st century. Why does the past persist into the present, and where do we look for it? Facing an explosion of options and influences unprecedented in Tibet[2] and in diaspora communities, sustaining cultural identity is difficult. It requires an evaluation of the relationship of individuals and communities in the present to their conceptualizations of their past. This collective memory is vital to cultural identity and ways of envisioning the future. For these artists, a future as Tibetans is possible, though trying to imagine such a thing inevitably comes up against threats to linguistic, religious and cultural integrity. How does tradition remain relevant in a world of rapid change? This present congregation of artists is engaged in just this pursuit, questioning through images what to keep, what has become emptied, what is even possible to transmit to future generations, what is vital.

The flood of influences from outside cultures and the marketplace of globalization may also be a cause for hope and excitement. As Rossi & Rossi’s spectacular collection of religious arts from the 13th to the 18th century, from far western to eastern Tibet, demonstrate, it was precisely Tibetan artists’ extraordinary capacity to invite, study, and master techniques from their borders, and re-fashion them within a distinctly Tibetan environment and aesthetic, that has created an art tradition world renowned. Throughout Tibetan history, the cultural spheres of philosophy, religious practice, astrology, medicine, and art have been imported and incorporated with indigenous knowledge to create unique Tibetan systems that perfected these arts and sciences. Are we perhaps witnessing the initial phase of another period of tremendous creativity in Tibetan culture, as foreign materials, techniques and styles merge with traditional ones, each to be put to novel purpose in expressing a Tibetan view of 21st century encounters of tradition and modernity? This may be too simplistic and optimistic, but certainly in the waves of Indian Buddhism that flooded Tibet twice[3] there must have been those who cautioned against the foreign ideologies and feared the loss of indigenous knowledge.

If we ask what makes these Tibetan artists, at this moment, quintessentially modern – they are after all working with traditional motifs, beliefs and icons – it is not merely that they are painting in the 21st century. Nor it is merely new styles and mediums which merit the appellation of modern. In addition to these, it is the way their art functions, and the changing conceptions of the role of the artist in society which are radically new in Tibetan culture. It is evident that they are rooted in and committed to their culture, though sensitive to its changing manifestations from the 13th through the 21st centuries and into the future.

Tibetan artists have used for this exhibition the visual language of Buddhist imagery for commentary, critique and description of their world today, as we shall see. Tibetan art has always reflected a vision of the forces in the universe, and here that function of art continues, but strikes closer to home, becoming personified, offering social critiques, and visually incorporating our media saturated era. Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are brought down from the celestial abodes of the antique thangkas and situated, for better or worse, in our human realm. Perhaps those palatial realms envisioned in the past no longer feel like a realistic representation of the structure of the world, perhaps their presence in this human realm is rich enough for the imagination. In any case, we meet the Buddhas through the lens of contemporary history and life.

II.

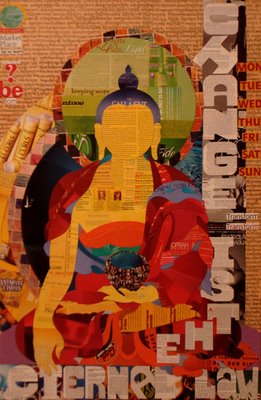

The complexity and variety of contemporary arts occur within a harmonious aesthetic. Here we may begin to see continuities with the past, for traditional arts valued the balance and harmony of composition, color and technique, from overall whole to the minutest detail, whether the subject be ferocious or munificent. Thangkas in the Rossi & Rossi collection of Manjushri (13th c.), Amogasiddi (Late 13th), Buddha Shakyamuni (14-15th) and the Life of the Buddha (18th) impress viewers with a central image that emerges strikingly from an intricate environment. Swirling colors and intricate details in contrast with the clarity of a single Buddha seem to have influenced the contemporary versions by Tsering Nyandrak and Tsetan (Buddha), Tenzin Rigdrol (Buddha Manifested for Ad and Change is the Eternal Law), and Gonkar Gyatso (Buddha Shakyamuni). Whereas thangkas occupied a central place in the visual culture of pre-20th century Tibet, in today’s globalized sites this position of primacy has been co-opted by advertising. Nyandrak’s billboard design and Tenzin Rigdrol’s magazine advertisements reinstate the Buddha into contemporary visual prominence, drawing upon thangka’s visual technologies. The four part poster series by Nyandak and Tsetan suggest ambiguous modern mudras, perhaps of the grasp of a wrathful deity or the human clawing at acquisitions, perhaps the turning of the wheel of dharma or an ‘OK’. The startlingly graphic quadrant, with half a Buddha’s head swirling with blue and green against a bright red field, combines precision (a hallmark of both thangka and computer technology) and the natural or random appearance of water or weather. The serial use of the black and white line silhouette suggests a form which may be filled with any content we wish.

Tenzin Rigdrol’s Change is the Eternal Law expresses one of the fundamental principles of Tibetan Buddhism: the nature of all things is impermanence. Despite this fact, we often operate as though we and our possessions and the objects of our desire are permanent and promise lasting happiness. Tenzin’s lesson in impermanence hopes to drive home this fact of reality through the use of the extremely ephemeral – hair products, glossy weekly news magazines, and snack foods. And yet the figure of the Buddha stands like the geometric structure that remains constant in a shifting kaleidoscope, reminding us that the possibility of escape from suffering and rebirth is also a perpetual feature of samsara. The Buddha’s appearance is updated, up to the latest newspaper and Oprah magazine, and in the process the Tibetan text in the background becomes equated with the English texts as no more meaningful or lasting. Yet in the external change to current fashions and lack of facial features, the inner qualities of the Buddha seem to transcend cultural or temporal bounds. The meditation posture, mudra, bowl, robes, and halo remain, just as the central events of the Buddha’s life and teachings that they mark retain relevance today. Tenzin Rigdrol’s present location outside Tibet, and the title of the piece, suggest too a paradoxical struggle: to maintain a core identity in the midst of competing influences is possible on the one hand, and yet there is the law of impermanence on the other.

With similar technique of the whole being in the details, Gonkar’s pop stickers on paper coalesce into the form of a Buddha, a shape he has said he has loved working with over the years of his career. His modern Buddha sports a halo like the Statue of Liberty’s crown, and the thangka painter’s proportion guidelines, which traditionally follow strict measurements and are subsumed beneath the paint in the final stages, remain visible and converted into New York’s grid of city blocks lined with pollution-emitting vehicles. Radiating fighter jets from the Buddha’s head connect NYC with the rest of the world at war; among the glittering stickers dwell a soldier, a suicide bomber terrorist, a helicopter and tank. For Gonkar, bringing the Buddha “from the 14th century into the 21st century” to show “contemporary times and popular culture” means to make a connection with the war raging in the Middle East, multi-culturalism, and the more light-hearted affairs of daily life. The cultural diversity of the global present illustrated in his mass of stickers also incorporates his personal experience with geo-cultural hybridity through the inclusion of Tibetan letters (which spell the auspicious greeting ‘Tashi Deleg’) and a Socialist Realist Chinese propaganda figure from the Cultural Revolution era. Gonkar introduces humorous amongst his characters, such as one who reclines and says “I wish to become a Buddhist monk so that I don’t have to go to school.” A donkey near the bottom says, “I know Mr. Shakyamuni. I met him at the Sunday market in East London.” In Gonkar’s unique vision, the serious issues of our times seamlessly co-exist with the fun and playfulness of life.

III.

Since Duchamp, artists in the West have taken on the role of social critics, protesting the art world as much as the foibles of society at large that surround them. The traditional roles for artists in Tibetan culture have not included such fierce independent and controversial thinking, and mid-twentieth century Chinese politics radically inverted the western stereotype of artists by enlisting them in Communist revolutionary ideological battles as ‘art workers’. Charged with drawing source material from the people, they also led ‘mass art’ movements by the people with large character posters of political slogans and depictions of Mao, heroic peasants and workers. In Tibet, former thangka painters spent the Cultural Revolution either adapting their meticulous technique to the broad brush strokes of Socialist Realism’s utopian vision, or, recognizing that to paint anything else meant severe punishment, did not paint at all. One of the first art prizes awarded to a Tibetan after the Cultural Revolution went to Amdo Jampa (1914 – 2001) for a realistic painting of a simple wooden tea cup; those who had returned more swiftly to thangka were not similarly rewarded. In light of such 20th century history, when oppositional views in art went from culturally idiosyncratic to criminal activity, and approved art practices only slowly re-admitted indigenous culture and religion as suitable subjects, the confident social and global criticisms offered by Tibetan artists today is radically new. Particularly in the TAR, where criticism is not politically tolerable, creativity can become a powerful method of communication.

Similarly unprecedented, artists today are skilled in capturing and illustrating their perceptions, critical or not, of their human society. This exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity for Tibetan artists to reflect in very personal ways on the history and status of Tibetan arts and culture and its relationships to the local society and in the international arena. For most artists, the project becomes a study in objects’ changing meanings over time and in different locations.

IV.

Social commentary in these pieces works on several levels. Critique of the commercialization of Lhasa and the increasingly worldly attitudes of its residents is expressed as one side of a coin, the other side of which is a perceived degradation in religious practice and cultural knowledge. For example, Tanor finds the world of religious merit and the world that surrounds him to be at odds, with global politics and rising personal economic and material desires making it “increasingly difficult to be a religious person, or even a good person.” Tanor identifies with the monk who gazes upon a mix of religious symbolic devices – the stupefying ram wheel from a tantric manual in the Rossi collection, the wheel of life and the mandala – in all of which central elements are replaced by contemporary fallacies. A man, whose form is filled with Tibetan motifs and stands for Tibetan culture and religion at large, kneels in a pose of surrender, adapted from current wartime practices in the Middle East; this, Tanor explained, is the moment before execution. To express the past in this way seems, as Walter Benjamin wrote, “to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger.[4]” The danger is to tradition and its recipients, that its life will be co-opted by the ruling powers and dominant influences; the challenge to the person of vision is to resist the power of conformism while maintaining an unreasonable hope.

Sonam Drolma’s view from Switzerland indicates rising consumer desire and faltering spirituality is far from a uniquely Lhasan problem. Her The Gods are Victims empathizes with the deities’ reversal of fortune; from a society which devoted considerable material wealth to the veneration in temples, rituals and thangkas of enlightened beings in their celestial abodes, today material resources are first siphoned into commercial and political visions of progress. The mantras in the Rossi & Rossi Amogapasha black scripture have morphed into gold hued tire tracks, as though run over on the road to progress. The deities look to have long abandoned their niches, but where have they gone?

Other artists in this exhibition aim their critiques beyond the Tibetan world to global politics and international art practices. Kelsang Lamdrak has been working in Switzerland with multi-media and installation pieces. Recently he has been transforming ordinary beer cans into tunnel visions that amuse, and play games with our perspective. Peering into the opening in the top of the aluminum can, pinpoints of light enter from the illuminated bottom of the can to reveal miniature scenes of greater magnitude than their form or size would suggest. In these views, reproduced and enlarged as C-prints, Kelsang Lamdrak turns the 17-18th century pages from a tantric manual’s[5] instructions for the imprisonment of enemies within ‘wheels’ into contemporary satire. George W. Bush is encircled within the Maddening Wheel in the clutches of a monkey; Hu Jintao is centered in the ram’s Petrifying Wheel. After a good laugh, lest we think such spinning in negativity is reserved for today’s Presidents, Kelsang reminds us we too are subject to the mental poisons by providing an Empty Wheel “for your own problems”.

Panor (Tsering Namgyal) and Dedron offer commentary on their materials as keys to unlocking the deeper implications of their work. The main material is leather, taken from the nearly worn out soles of a pair of discarded traditional Tibetan boots. To this husband and wife team, the soles represent the footprints of many successive generations that have gradually accumulated to form their Tibetan culture, step by step. Secondly, they use the soles to demonstrate that, from a Buddhist point of view, placing the image of a Buddha on the bottom of the feet is considered very sinful, yet in this modern world changes in attitude locally and different customs abroad have enabled people to see Buddha statues and images as just another material thing which can be bought and sold. The two Buddhas in the pair are discussing (or they are reporting other people’s commentaries), just this fate, in the global language of English. One asks “Is this your first time to be here?” “Yes,” the other replies, “it is a wonderful place. Where have you been before?” The first replies, “I’ve been many many places like Tokyo, London, Sydney.” They also ask each other their age (“very old”), and the cost of each other’s ‘performance’ (“it’s a secret”)[6]. The third Buddha displayed between and higher than the other two is different. The turquoise at this Buddha’s heart is a bLa gYug, a stone that holds and protects the spirit, commonly worn by Tibetan people. This Buddha has not lost its essence and blessing power, and the mantra around it, resembling a carved mani[7] stone, indicates its physical location as within Tibet, as English connotes the rest of the world. Dedron and Panor also explained that for them, the dangling mirror[8] is one of the most important materials of the piece. It is the nature of mirrors to show, without bias or distortion, reality before it; mirrors cannot lie. The mirror hangs from the central Buddha in Tibet, as a marker of truth and honesty, while from the other two dangle mani counters. Taken off a rosary and attached to discussions of value, we have to wonder what they are counting now. Finally, the left and right pieces have stitches holding together the Buddha and the sole (generations of tradition) like an open wound that will not heal. In contrast the Buddha in Tibet is suspended in graceful equanimity.

Pewang (Penpa Wangdu) brings the materials and techniques of traditional thangka painting to his modern works, asserting that contemporary Tibetan art, for him, should be built firmly on uniquely Tibetan methods and especially pigments. In his studio is a beautiful large wooden case filled with dozens of small shallow clay bowls containing a rainbow of stone ground pigments, some moist from recent use, others caked and dry, awaiting re-mixing with water. The gold and silver he uses are made for Pewang by the one remaining family in Lhasa that still knows how to produce paints from precious substances[9]. Pewang’s commitment to preserving Tibet’s methods and materials and his deep studies of art history inform the present work in this exhibition.

Pewang’s work Title? can be read as a critique of the history of Tibetan religious arts in recent centuries, in which sections of murals, altars and statues have been stolen or bought from their original context, sites here stripped bare until only a lone perfect Buddha statues remains. This prize piece for the international antique market, though bereft of context, is already marked with the red sticker of a buyer. As figures and ornamental pieces acquire the green sticker of deliberation, the red ‘Sold’ sticker, and disappear, gold coin-like circles take their place (the silver in the last painting is intended to remind us of the sun and moon in the upper corners of thangkas). This transition illustrates the title, and viewers’ changed ways of seeing The sight of a Buddha no longer arouses faith, but thoughts of monetary value. Many citizens, not only artists, are deeply concerned by the lack of protection for their cultural and religious antiquities, many of which are still revered as sacred beyond their material value[10]. Pewang combines deep knowledge of Tibetan traditional materials, techniques and art history with a sense of humor to express this contemporary concern and critique.

V.

In addition to the role of the critic, artists also often hold up a mirror in which society recognizes its own reflection as though for the first time. Several Tibetan artists captured and portrayed an astute perception of their environment, describing, more than critiquing, their world.

Gade has a keen ability to offer a whimsical take on the mix of Tibetan and global cultures, while also asking us to consider the implications of rapid and radical social change. Gade often uses humor by juxtaposing contexts we don’t generally think of as co-existing, but in fact are. His Black Scripture (dpecha nagpo), influenced by the gold [11] lettering on black of Rossi and Rossi’s Amogapasha scripture, lets us imagine a page from a tantric ritual manual with symbolically shaped diagrams and mantras. Upon closer inspection though, we find a star inside a circle and triangle jumbled with the names of British rock bands, a mandalic shape orienting us not to the layout of a deity’s palatial abode but to the dominant political and religious ideologies heard about or subscribed to in the PRC, and a grid resembling a stylized verse of religious poetry turns out to be Chinese language introductory phrases for learning colloquial Tibetan[12]. These details seem to displace Tibetan Buddhist prominence, while showing the pervasiveness of imported materials and creeds. The long scroll with a thick wooden dowel at the bottom, as well as the tiny cut out windows and coin shapes, refer to Chinese fine art traditions, but the shapes and texts signal Tibetan religious arts. It is not merely a mix of Chinese and Tibetan artistic traditions, but a mix of cultures, religions, and politics that ultimately, while beautiful and interesting, lacks any meaning. The words of the text are non-sense; the ancient Buddhist symbols are detached from their former meanings[13]. The forms are recognizable as traditionally Tibetan, but beneath the surface, they have been vacated of meaning. Gade’s concern isn’t to resurrect the traditional meanings, but to show the superficial level of knowledge most people, Tibetans or outsiders, have about Tibetan culture today. For me, this is also conveyed by the gap that bisects the images, which our brain works to re-assemble, yet accepts for its aesthetic power, especially from a distance.

Jhamsang’s Century of Change is a more personal analysis of the present, but envisions a future with broader social possibilities. Jhamsang explained that at present, he has no idea how to communicate with the Buddhas, through meditation or any other means. But with the future’s powerful advancements in computer technology, we may yet be able to communicate speedily and directly with them! Jhamsang was drawn to Rossi and Rossi’s Amogasiddhi thangka because it reminded him of the colors and shapes at the contemporaneous Shalu monastery[14]. For this work, he made some changes to the original, most dramatically in simplifying the color palette from greens, blues, reds, oranges and yellows to primarily high contrast dark blue and yellow. He also changed the facial expression of Amogasiddhi, reversed the hands in the mudra and added more shading. His deep respect and admiration for the tradition, and a unique period in the history of Tibetan art, shows, but so too does his belief in the need for continued innovations and development in Tibetan arts. His layering of shinny metallic silver computer chips and circuits in delicate tracing over the Buddha’s limbs and adornments, radiating out to connect with other ‘components’ in the system, far from obscures the figure of a deity, as conservatives might charge. As Jhamsang told me, it is not contemporary artists’ job to be photocopy machines replicating images from the past, but to continue to develop Tibetan arts as a tool for expression of the thoughts and feelings of today. Though these feelings include a presently unbridgeable gap between the personal and the enlightened, the conjoining here of past and future technologies comically and profoundly expresses compatibility and hope.

Tsewang Tashi firmly believes that to create contemporary art, contemporary life cannot be ignored, especially in favor of outsider’s mythic visions of Tibet. Since 2003, Tsewang has turned from drawing inspiration from the physical environment to photographic portraits of real people. He collected photographs of random college students and then manipulated them on a computer to enhance the lines of light reflections and alter their skin tones to the neon and synthetic colors which have become naturalized in Lhasa’s urban development. These portraits of youth, in everyday city dress, painted larger than life against a stark white background, create a powerful contrast to the typical image of Tibetans found in tourist souvenirs and advertisements. In fact, it is sometimes even hard to tell that they are Tibetan. Facing us with a direct gaze, absent of turquoise ornaments, yaks or other “traditional” accoutrement, we are forced to confront our own Shangri-la informed expectations, pitting our imagination of a past against present reality. Buddha No.1 2006 transfers the same techniques to a close up view of the face of a 14th century Buddha statue form the Rossi& Rossi collection, but with surprisingly different results. Tsewang met with a few challenges: metal and flesh reflect light differently, and the statue’s features are much more sharply defined than in his human subjects. Blue, “a peaceful color”, accords with the Buddha’s continence, and Tsewang saw in the roundedness of the face a wonderful Tibetan character that emerged in the arts after the various Indian influences had been subsumed. Tsewang’s versatility makes explicit artistic inversions involved in bringing the Buddha into the human realm and vice versa. Tsewang’s application of the same techniques works differently: the shock of multi-colored people disappears when confronted with a blue Buddha (Buddhas come in all colors except human ones), recognizably Tibetan identity becomes paramount rather than obscured, and color becomes more of a reflection of inner quality than an external environment.

Penpa Chungdak’s (Penchung) work was inspired by the 13th -14th century thangka of Vajravarahi in the Rossi & Rossi collection. He painted a miniature version of the thangka in the center of the left side and on the right side a much enlarged detail of the fingers of her hand which holds a skull-cup. Penchung states “the piece reflects a Buddhist approach towards the relation between the smallest particle and the universal. Our mind can have a similar approach.”

The contrast between the close-up details and colors of the right side with the open blank left side Penchung sees as an expression of the Buddhist concept of emptiness, the inherent nature of all phenomenon. He also remarks that this split, combined with the loss of sharp focus on the right side, “represents what we feel very strongly about but are unable to express.” When we act on a desire to see every detail, to get as close as we can, we often expose our inability to access a deeper knowledge. Penchung seems to capture a Tibetan yearning to deeply understand the smallest elements of tradition, but zooming in only pixelates them, and perception becomes more blurred than clarified.

VI.

Two artists were inspired, in very different ways, by the experience of viewing and responding to Rossi & Rossi’s traditional collection as a whole. Nortse (Norbu Tsering) was overpowered; confronting the stellar arts of the past is also a poignant reminder of all that has been lost. Black Sun Red Sun questions the possibilities, or impossibilities, of Tibetan culture reassembling itself in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. It is a courageously strong statement about the lived reality of that time, and its ongoing ramifications into the present. These days, common rhetoric of great suffering in all of China during the Cultural Revolution tends, when focused on Tibet, to lament the destruction of monasteries and statues. At the center of Red Sun, a headless Buddha bronze statue, subsequently purchased in the Barkhor, attests to this destruction. But Red Sun, with its red veins scattering blood in all directions and clear spherical tears surrounding the ruin of Shakyamuni, also commands memory and history to the destruction of human life and cultural life. Black Sun images the fear that Tibetan life has been forever changed and something in the collective heart shattered beyond repair. Nortse reflected on the meaning of the materials, saying the red blood spilt has dried and turned black, the Buddha shape is formed of broken glass and some barley seeds. To rebuild after a culture has been destroyed, scattered and lost is, to understate, very difficult. At this late date comes an unprecedented expression of sorrow and dread, mitigated perhaps only by the use of completely Tibetan materials and the present cultural life within which they circulate. Two tiny red feet on the handmade paper represent the path tread so far; one looks down in horror upon all that has been trampled under foot, but perhaps too has the choice of how to proceed from here. Finally, Nortse urges that inevitable movement into the future not forget the sufferings of the past.

Palden Weinreb, in contrast, seems to have been struck with the consistency, from the 13th through the 18th century (and beyond, even into Gonkar’s contemporary work), of the guide lines for the properly proportioned Buddha. In traditional scriptures, aesthetic and religious criteria establish the strictly taught forms of deities. Failure to create the proper physical support would hinder an image’s ability to host the energy emanated by an Enlightened being. Such a sin harmed the viewer, as well as condemned the artisan to a hell realm. On the contrary, the proper and beautiful image has the power to calm the mind, enhance faith, and even ‘liberate upon seeing.’ Edifice reminds one of searching for constellations in the night sky, connecting the dots to reveal some innate universal structures, as the Buddha’s proportions invisibly underlie centuries of riveting beautiful religious creation and powerfully affect our stream of consciousness over countless lifetimes.

VII.

Losang Gyatso’s vibrant electric green ‘AH’, a syllable associated with Amogasiddhi and primordial sound, is especially jarring amidst this exhibition’s many stone pigments and softer color palettes’ harmony. Gyatso explains that in the bardo, the passage of consciousness from one life to the next, the sight of “violent” shards of green light appear intimidating and threatening compared to the “womblike” warmth of softly glowing reds. Yet the spiritually advanced consciousness recognizes the paradox and fearlessly ventures outside the “comfort zone,” and into the realm of Amogasiddhi. A radical re-invention of the late 13th century thangka, in which the green Amogasiddhi sits surrounded by red toned attendants in a red palace, the intensified color also conveys heightened emotions and passions about how to die and how to live. Gyatso states “the path towards something truly new is not” necessarily easy and requires us “to step out of our comfort zones. I like this idea because choosing to be an artist is neither easy nor comfortable.”

In these contemporary works, the Buddha is used as much as a visual language as a religious symbol. So much is communicated through the shape, materials, and colors; the Buddha stands in for the diversity in Tibetan culture, and in the artists’ contemporary experiences.

Artists’ contemplations of the relationship of the past to the present led to expressions extremely personal and broadly felt, from the satirical to critical to inspirational; encompassing and merging pride and despair, spiritual ideals and human weakness, creation of beauty and its destruction. These images communicate to us that to be Tibetan today is to dwell where the duality of emotional experience within a single moment of feeling is not extraordinary. Yet I find their ability to reflect upon and so eloquently express this experience, of a time of rapid cultural transformation, remarkably extraordinary.

[1] Leigh Miller Sangster is a Ph.D. Candidate at Emory University (Atlanta, USA) in the Institute for Liberal Arts program in Culture, History and Theory. She is presently conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Lhasa, and spoke with many of the artists in this exhibition about their work for this article.

[2] For purposes of this essay, the place of “Tibet” refers primarily to the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the artists in this exhibition living in the PRC are from Lhasa. In contrast, “Tibetan” traditional Buddhist arts and cultural identity broadly refers to the Tibetan cultural world.

[3] The First and Second Diffusions of Buddhism, in the 7th – 9th and 11-13th centuries respectively, aroused such anxieties that a King was eventually assassinated (the 42nd dynastic ruler of Yarlung, Lang Darma in the 9th century) and sectarian religious and political power battles raged.

[4] Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” section VI, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt. NY: Schocken Books, 1968.

[5] In the Rossi & Rossi collection, wylie

[6] When a Tibetan friend pointed out minor grammatical mistakes and misspellings, they were justified by Panor: “It’s ok. English is not the Buddha’s first language.”

[7] Tibetans often refer to the extremely popular mantra of Chenresig/Avalokiteshvara, Om Mani Padme Hum, as simply ‘mani’.

[8] These copper pieces, often worn on the belt to ward away hindering spirits or obstacles, present the animals of the zodiac and other Buddhist cosmological symbols on one side, and a smooth surface etched with an ‘Om’ on the other side. Before the arrival of modern mirrors in Tibet, these served to show one’s reflection.

[9] This family is Tibetan and produces paints from pure gold, silver, coral, turquoise and copper for use by thangka painters, gilding statues such as the Jowo Shakyamuni in the Jokhang, and in the past made the paints even for the ceiling and column designs for assembly halls and chapels in the Potala. This craft is difficult to learn and laborious, and the secrets of production have only been passed on via generations.

[10] Expression of this sentiment was publicly aired via a televised comedy routine by the famed and beloved comedian pair, Thubten and Migmar, and recently re-staged in an English adaptation by young adult community volunteers for an arts festival. Artists have joked with me about going for Buddhist pilgrimage to the West and doing prostrations in museums and galleries!

[11] Today the ink appears gold hued, although it is actually oxidized silver. In the past, both gold and silver and other precious materials were used for special editions of scriptures, as can still be seen in the Potala and other sites.

[12] In the mandala shape in the middle, the central symbol is the hammer and sickle of the Communist Party, the strongest ideological influence in Lhasa. In the four directions are the American dollar symbol, the Muslim star and crescent, the yung drong Bön and Buddhist symbol of auspiciousness, and the Christian cross. In the mandala’s gates, a thermos is an example of a material product that initially came from the west to China, yet is no longer used by foreigners in their homes while has become ubiquitous in Tibetan homes. This is similar to the travel of ideas, such as Buddhism which came from India, where it died out, but grew strong in Tibet. A Coke can is another ubiquitous product in modern Lhasa. The Golden Urn has come from China to be used for the selection of Tibetan lamas.

In the poetry section, Gade uses the form of religious verse in which syllables may be read horizontally and diagonally, offering profound meanings and extremely difficult to compose. Here, diamond shaped lines of Chinese phonetic characters that are pronounced like Tibetan sounds are written as if copied from a Chinese textbook for learning colloquial Tibetan. The top line says pu (boy), then gu coom tsang (greetings), then kyerang gi ming ka re red? (What is your name), chimpa ngarmo red (the urine is sweet, a humorous reference to traditional Tibetan medical analysis), then kyerang gi ka nas yin pa? (Where are you from?), and at the bottom, mo (girl).

[13] Some Buddhist arts correlate geometric shapes, elements, colors and mental states, etc.

[14] Also contemporaneous with Marco Polo’s adventures in Yuan Dynasty China, Jhamsang noted.