Dear family and friends,

I hope all of you are enjoying life and the change of seasons. Though I have been a horrible correspondent in the past many months, I am writing now about

my most recent journey in hopes of reconnecting with some of you, and giving a fuller picture of our life in Tibet to all, despite being somewhat impersonal in this medium.

This letter is just about our adventure to far western Tibet; the few photos here are Jason's. You can see my photos of all these places at

http://picasaweb.google.com/leigh.sangsterJason and I traveled for two weeks with my amazing friend of ten years some of you know, Christy Cline, and her friends, a college friend Matt, and a fellow naturopathic student, Marit. Christy just graduated from Bastyr with her ND and specialization in acupuncture, passed her boards, and will be opening a general physician/acupuncture practice in Carefree, AZ this year. I am so honored that she chose to celebrate her accomplishments by coming to Tibet, and with felicitous aspirations to hike the kora of Mt. Kailash. We wouldn’t have done it without her initiation.

This is our story of two magnificent weeks in a 1990s Land Cruiser, during which time we had two showers (the washing kind), blew three tires, exhausted one car battery, navigated a pass in a snow storm, slept five to a room (not counting the mice) every night, tried not to spend longer in a toilet than we could hold our breath, and ate our fill of instant noodles and meal replacement bars. We saw the most incredibly remote and immensely gorgeous valleys of Tibet I have ever seen. Sparsely populated by humans, they were full of herds of wild and domesticated animals, which sometimes stood nobly and returned our gaze as we passed, and sometimes gave to hilarious darting, leaping and scrambling in front of and around our brake-grinding vehicle.

(The official animal list: Yak, Dzo (a cow-yak cross breed), cows, antelope, gazelles, wild asses, donkeys/mules, ducks, eagles, ravens, lots of little birds, hares, pica (plateau marmot-type animals), sheep, goats, dogs (including mastiffs), mice, lizard, and, in the lower elevation towns, pigs and chickens.)

We drove three straight days under vast blue skies to the town of Darchen, near the holy Lake Manosarovar at the base of Mt. Kailash (Gang Rinpoche and Gang Tise or Precious Snow Peak in Tibetan; Kailasa in Sanskrit). Darchen is about 800km from Lhasa, in the far western province of Ngari, in the southwest corner of the Tibetan plateau. North lies the former Silk Route and Kashgar in Muslim Xinjiang, south is western Nepal, southwest are the Buddhist Himalayan areas of India- Himachal, Spiti, Lahual, Ladakh, and Geshe Lobsang’s hometown in Kinnaur. From an elevation slightly higher than Darchen, we saw sun rise on snow peaks in Nepal, India and Tibet.

Kailash itself, at 50 million years old, rises alone

to tremendous heights that tower over the immediate range of lower “hills” that are only 20 million years old (and 5000 m high). The shape of the mountain has been liked to a crystal and a pyramid, and the sheer walls with their distinctive snow and rock striations certainly captivated us, evidencing the pull the mountain has exerted on pilgrims for centuries. Hindus revere the mountain as the abode of Shiva, and the Indian government manages an annual lottery to limit the Indian pilgrims to a lucky several hundred quota set by China. Bon (pre-Buddhist indigenous religion of Tibet deeply connected to the local environment and spirits therein which has over time adopted Buddhist philosophies) adherents see the mountain as the site at which their founder descended to earth to teach and the place of many miracles performed by their lineage of masters. They circumambulate in an anti-clockwise direction, setting them apart from the clockwise moving Tibetan Buddhists. Four of Asia’s most important rivers also begin here. Most would know these rivers by the names they acquire as they pass through India, though they’ve traveled through Tibet, Pakistan, Bangladesh and elsewhere too: the Brahmaputra (which comes almost to Lhasa before turning south), the Indus, Sutlej, and Karnali (which becomes the Ganges sacred to Hindus). In Tibetan, near their source, these rivers carry names of animals (lion, horse, elephant and ?), which combines with the other sites named for deities, elements, and the precious stone faces of the mountain to create an overall sense of a blessed, cosmologically complete, condensed perfect universe. It did seem that the surrounding areas had a vast emptiness and even harshness that the immediate valleys that comprised the kora around the mountain did not, vibrating as they were with more animals, grass that clung on to green longer, colorful rocks and streams, and of course the residual energy and signs of centuries of pilgrimage.

We spent a day in Darchen arranging the kora hike: learning the process of hiring yaks, and mentally and physically anticipating the Drolma-La pass, the highest point of the kora at 18, 760 Ft. (5660 m). Previous record elevations for me have been memorable. There was my first big pass at 11, 500 ft. on my first Himalayan trek in 1996 to Chialsa, Nepal; second Nepali trek in Dolpo brought me to a lake at over 15,000 ft, and a previous Tibetan hike which crossed 15,500 ft. Points over 16,000 ft. I have only reached in a vehicle on roads in Tibet. Clearly, the Drolma-La was a significant gain, and we’d be walking. Despite my acclimatization to Lhasa (under 12,000 ft.), the effects of altitude gain are never predictable, and we were feeling a little trepidation. This explains the bottles of oxygen we brought, and the need for yaks to carry them, our food, and potentially us!

Since I was the only one of the group who could speak enough Tibetan to communicate about yaks and packs, I got to be an honorary male and join the other groups’ guides and drivers in the yak men’s “office”. Prices, meeting point and time, payment for sending off of a messenger on a motorcycle to summon a yak man and three of his beasts, and so forth were all negotiated. I asked if the man I was dealing with would be coming with us, which brought all kinds of scoffing and laughter: wasn’t it obvious to me that he was the Leader? We latter learned he was pocketing quite a bit of cash; obviously a leader. He put his red fingerprint on a ‘receipt’ which he instructed me to give to my husband, and announced we were done. I’d become female again!

We’d spent several hours the night before getting some walking exercise around the small town on a slope while looking for elusive the Om Café, rumored to have yak steaks and French fries. By night it was a lost cause, but the next day we triumphed – no steak, but we learned how long it takes to deep fry potatoes over a yak dung fire (a long time!).

Day One of the circular kora hike:

We rose early, before the sunrise (according to Beijing time, about 8 am), and had a breakfast of instant coffee and stick-to-your-ribs tsampa (roasted barley flour mixed with tea to take a form between porridge and play dough, depending on your preference). We walked out of the village to the base of a hill to the west, which we followed as the sun’s first rays hit the snow peaks across the turquoise lake. In the sublime beauty, we each summoned to mind our various motivations and hopes for the kora and walked in silence. Our first view of Kailash from the kora route was designated the First Prostration Point, marked by piles of small stones and strings of colorful prayer flags. We turned north here into a valley which narrowed as the mountain sides towered above. A few hours from Darchen, we stopped at the seasonal tea tents run by local women in the distinctive Ngari chubas of bright bold stripes of colored felt and wool. We waited here for our yak-man and three yaks to come down from the north and our driver with the jeep to come up from the guest house with all our bags (this is as far as a car can go). Though the sun had risen, we were back in chilly shadows and the wind carried glacier cooled currents, so the warm of the tent was welcome already. Though I am, after ten years, totally ‘acclimatized’ to the taste of yak butter tea, every time I taste it outdoors after a walk or in the cold weather, I fall in love again. For the less accustomed, here is rule of thumb my friends deduced: the higher the altitude and the colder the weather, the better the taste! The tea is like a broth of everything the body needs; black smoky tea concentrate, boiled water, salt and butter churned in a big wooden tube (or, in Lhasa, an electric blender). (actually the butter is from dri, the female of the species – to Tibetans, ‘yaks’ are male, so our claim to be drinking yak butter tea is humorous to them. But there’s nothing funny about butter – it is a valued staple, and copious fresh amounts are piled on honored guests – not literally! - in tea, tsampa and food.)

Our warmth, inside and out, at being in the this tent with a delightful little girl who insisted we all mime and do funny face tricks soon turned to heartache as I translated for the mother her questions for Dr. Christy. She complained of monthly swelling and pain in the lymph area under her arm and of headaches and cramps. After advising her to use alternating hot and cold compresses for the swelling, she explained to me how this condition began four years ago. Her second child had died, and complications with her third pregnancy brought her to the nearest large town’s hospital, staffed by Chinese doctors. She knew many Chinese women went there for abortions, but did not know what her “treatment” would involve until it was too late. Her pregnancy was aborted and she showed me the place inside her arm where something she didn’t understand was inserted. Since then, she had not been able to get pregnant and menstrual cycle was irregular and full of physical pains. Tibetan women have been subjected to forced sterilization and abortion for decades, but the practice, throughout China generally, is supposedly discontinued. Minorities in China, Tibetans included, and especially rural dwelling minorities, are allowed more than the One Child policy urban Han are supposed to adhere to, so even according to the rules of the practice, she should have been allowed a third child even if the second one hadn’t died. Now she only has one daughter, though many nomads, like her family, have 7-8 children these days. “Allowed” a certain number of children is such a hard concept for us; women here have asked me how many I am allowed in the US and have trouble believing my answer of as many or as few as I wish. But this kind, quick to smile, shy woman was clearly grieved, and whatever in her life might have given her a sense of justice and injustice seemed to be telling her this was a case of the latter. We had to leave then, and she refused to let us pay for the tea! I thought I managed to sneakily leave some money on their small altar, but a few minutes later, the daughter came running out with a big lump of butter in a piece of plastic for our tea making on the road! They’d be moving camp soon, but we were sincerely welcomed back to that spot next summer.

Desperately needing to pee after so much tea, I struck out ahead of the yaks for some rock cover.

We walked for approximately 5 more hours, mostly spread far enough apart to enjoy our own thoughts and the silence, but close enough to stay within site of at least a few in the party. The thin stream which we followed up the valley was frozen in many spots, creating delicately beautiful patterns of ice, rock, grass and reflections. We gradually gained elevation, and the snow peak of Kailash came in and out of view, always from startlingly different angles of rock shape and glinting sunlight. The gourmet lunch item, when compared with my stiff cold Clif/Luna/GeniSoy/Balance bar, was peanut butter and biscuit, topped off with PowerBar Shot Block (cran-razz flavor) glucose gummy thing. Yes, we stocked up for this trip months in advance at REI.

Spotting the first night’s stop, I was eager to find a way across the widened stream to Drira Phuk monastery (female yak horn cave monastery), named for the dri which led a famous religious practitioner of the past to an excellent meditation cave here. The burnt red color of the building was visible from afar, but so dwarfed by the magnificence of the landscape around it, I wondered how humans have survived there for so long, while also appreciating the humility brought by recognizing oneself to be so small.

Enjoying the warmth of tea in a monastery kitchen, we looked out across the river valley to the awesome sight of the sheer north face of Kailash, and (!) the spectacle of our yak-man unloading our bags in the tent guest houses! Forgetting his instructions when he saw some members of our group stopped there for tea and photos, he settled in for the night and we had to make a second stream crossing. Tired and a bit shaky, it’s not surprising I got both feet icy wet, but fortunately we were near a warm fire to dry out socks and shoes, and the yak portage meant I’d brought a spare pair of shoes. (In the morning, we found the bridge, of course.) Instant noodles and Snickers eaten, we turned in early with two Nalgenes of hot water to warm our sleeping bags. Trying to drink 2-4 liters of water a day meant none of us slept through the night, but we were rewarded with views of the Milky Way in the early night and rising moon in early morning. Once I caught the reflection of yak eyes in my headlamp, a huge lump of fur and low grunting was waiting for morning.

Day 2: Our yak-man however was not so attuned to the coming dawn. He told us to start packing up at 7 am, as it would be a long day over the Drolma-la and on to the next monastery. We believed him since we hadn’t yet realized that he didn’t own a watch, and probably never had. At 7 it was still completely dark and no one was up and Jason and I went back to sleep. A fellow traveler in our tent cheerfully called out “Never trust your yak man!” but for those already up and packed and eager to go (marathon Christy and Matt) it was too late. When he was still snoring at 8, they woke Yak-man and the tent tea maker. Instant coffee and tsampa, quick run down of all the important sites along the route today and map check, and Christy and Matt were off for the day.

Within twenty minutes of leaving camp, we met our steepest incline yet, supposedly only a warm up for the ascent to Drolma-la several hours ahead. I was suddenly so lightheaded and dizzy and couldn’t catch a good breath. My head hurt and I was coughing more than the night before by the smoky fire. A moment of panic swept me as I questioned how I could ever make the rest of the ascent on my own feet, and I looked down on the approaching yaks, hoping they wouldn’t pass me too fast. Jason stood by and offered encouraging words and patience. My mind cleared enough to realize I’d hardly eaten any breakfast in my excitement and nervousness about the day, on top of usual lack of early morning appetite. Remembering my friend William’s advice to take as much time as I needed, I drank and ate and soon felt much better. Continuing on, I didn’t tackle the rest of the incline with the overconfidence I had initially, but found my own rhythm of breath and step and was soon in a mental zone of movement and the sound of my own breathing alone.

The path leveled at the symbolic Cemetery, Shiwatsel. Pilgrims leave personal items here both to make a connection with the place and the enlightened beings looking over it, and to go through a visualization of their own death and leaving this body behind. They often lay down on the ground as if a corpse, pray to be reborn in Chenresig’s Pure Land, and discard the past in the form of a piece of clothing, a hat, a lock of hair, a tooth…It was a powerful place. As I lay on the ground with chilly fingers and toes, I remembered Tibetan perception of the stages of death; the early stage of the retraction of heat from the extremities was feeling a little too real! The sun was warming though, and as I asked for help and guidance, powerful waves of blessings and images of enlightened ones filled my heart. Tears came to my eyes, and I was filled gratitude, calm, confidence, dedication and enthusiasm. I left a few inches of pigtails, and Jason and I continued on together, buoyant and energetic.

Yakman paused to let his charge graze on the last grass they’d see for a few hours, acknowledging that anyway, it was impossible to get them to move once they’d started munching. His family was all nomads, but he was quite proud of his 7 years of schooling, particularly his skill in math and Tibetan script, and passable Chinese. His sister-in-laws’ family frequently crossed the Indian border in search of good pasture, but always did so at night, fearful of the military stationed all around and their notorious jails. Needless to say he was also proud of having never been caught. We asked what his family thought of government practices in the last couple years of settling nomads in homes the government largely pays for, complete with TV, in exchange for some political statements of loyalty. The nomads pay their portion, sometimes 50%, sometimes less, by selling off parts or all of their herds, without long-term planning for their future income. The only skills they posses are in animals, wool, leather, butter, etc. and these villages of former nomads don’t create any local industry or train people for other work. Instead, located near highways with cheap food and goods, they are tempted into lives of passive TV watching consumers. Families are broken up, and herds and lands kept for one generation soon can’t be inherited by kids who grow up in the town ignorant of animals, or the new model of nuclear families small homes encourage breaks up herds traditionally and sustainably managed by brothers. With all these criticisms in mind, I was surprised he was in favor of a new home, with modern appliances and perhaps plumbing, and the newfound opportunity for kids to go to a school while still being able to live with their parents. Many have said before that the current state policies aim at converting, or at least pacifying, through material and consumer seduction. It’s a complex picture, and I can’t claim to know what’s best.

But, this wasn’t on my mind as we set off again, the yaks going straight up and us taking the switchbacks through karmic tests and pilgrim spots for various things. Mumbling all the mantras I know, I was perfectly happy and eager to see every spot on the map or I’d read about. Two Tibetan women, a mother and daughter, demonstrated the first few: a pile of stones one hangs from to weigh one’s sins (presumably if you pull down the pile, that would be really bad – I wrapped my arms around the top stone and lifted my feet off the ground – whew, didn’t budge); a round flat rock on the opposite cliff is known as the Karma Mirror (if you see white, you’re virtually enlightened, red and you’ve got some work left to do, black and you better start jogging this purifying kora!); a few holes in the sandy dirt from which they extracted and sifted earth until they found what they sought, strands of hair from the heads of dakinis, celestial females who assist spiritual practitioners and periodically gather for dance parties on this spot. The ladies were, like the majority of Tibetan pilgrims, planning to complete the kora in a long 15 hour day, beginning around 4 am and finishing after dark. We couldn’t keep up with their pace, nor Tibetans we later saw virtually running down a very steep mountainside!

We came in view of the final ascent to the Drolma-la and it was far less intimidating than I was imagining, but we still decided to stop for energy bars and dried fruit. Fortuitously, we realized when two young Tibetan men came along, we’d inadvertently stopped at another karma test. Several boulders piled up (left there as a result of a supernatural competition of athletic strength between two rival meditators, Milarepa and a Bon master) created a tunnel that is interpreted as symbolic of the bardo, the journey between death and rebirth we must all navigate eventually. This continues the theme of having ‘died’ at the cemetery, and journeying towards the rebirth the summit of the Drolma-la promised. In these tests, they always say skinny people with bad karma will get stuck, fat people with good karma will go through like butter. I got down on the ground and made it through the first section only to be baffled by how to continue. The guys started shouting at me to turn over, and then burst out laughing at me on my back. Clearly, I should have made only a quarter turn onto my side, and then I found a foot hold to push myself the rest of the way out and back to crawling with my elbows. Emerging did feel like some sort of victory! (Later we heard that Christy and Matt had observed a Tibetan woman, stuck, get pulled out backwards by her ankles! For some reason this discouraged C & M from making their own attempts.) The guys asked if we had any photos of His Holiness, which we did not. They pressed further – what about protection cords from Him? Again, I was sorry to disappoint them, but was able instead to offer some tiny pills that had been blessed by Him with the mantra of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara, bodhisattva of Compassion He is regarded as an incarnation of). This lit up their faces and, salvaging an old candy wrapper from their pockets, they were thrilled to take a small number home some to their families. Seeing as how I’d have been stuck in the bardo without them, there was gratitude all around.

We soon came upon a group of three pilgrims prostrating the entire way around the kora – three steps, prayer hands to forehead, throat, heart as body, speech and mind pay homage to the enlightened ones, and stretching full length on the ground, rising and repeating again. It takes about three weeks to get around the mountain this way, and with lots of stones, dust, and calluses along the way; the opposite extreme of the 15 hour version! We gave them each a small amount of money, but they were beaming before this anyway. Full prostrations and the devotion they suggest seem to be the hardest thing for foreigners to comprehend in their observations of Tibetan Buddhists. All I can offer by way of explanation is that I have observed their faces and movements to be full of confidence, determination, calm and patience, and also physical tiredness that doesn’t diminish the mental outlook. Such a means of cultivating humility, through regret of past misdeeds and motivation to be better, and reverence for those already excellent, does appear to bring results (why else would millions of people do it for generations across Asia?)

Returning to saying the mantra of Drolma, I continued. Drolma, or Tara, is the female Buddha most associated with protection from fears and aid in times of need or danger. She is also, in some forms, associated with the energy of accomplishing, that is the action side of fulfilling one’s goals and intentions. Motivation, or even wisdom, without action is not all that useful, but action unguided by wisdom and compassion is often dangerous, which is why Chenresig and Manjushri (wisdom) are the other two most popular enlightened beings in Tibetan Buddhism. The analogy is like this: a mother sees her only child fall into a deep lake. Because of genuine compassion, she has the unmediated impulse to save the child; but if she doesn’t know how to swim, her ability to help will be very limited, and if she knows but doesn’t jump, she can’t save the drowning one either. The Tara mantra comes in various lengths, but the short one is simple and easy to remember, and often when something vaguely threatening happens, like the engine of the ferry stalling while crossing a river or driving on a curvy road, you hear devout Tibetans switch from muttering Om Mani Padme Hum (Chenresig mantra) to Tara’s mantra. In this case, everyone, local or from far away, knows they need help getting up to 18,700 ft (5660 m), and there’s no doubt what’s on people’s lips. I can’t explain why or how it works, but it does. I felt I was being carried, my heart was so light. Needing to catch a breath every now and then was a delight in stopping to take in the scenery. Mantras matched steps and breaths, and before long we were at the rocky wide saddle strewn with thousands of prayer flags. In the center of the pass is the huge boulder which gives the pass its name. A virtuous practitioner was trying to discover the kora route around the mountain, and wandered astray into a side valley which would have been not only very difficult due to ice and snow, but also would have meant trespassing on the dakinis’ haunts. Twenty-one blue-green wolves appeared, and, since he was wise, he knew to follow them to the next valley and that pass. Of course, these were the 21 Taras in disguise, who revealed themselves at the pass by all transforming into their goddess shapes, merging into one Tara, which then absorbed into the boulder.

Previously in Lhasa I had been to visit a female psychic, for lack of a better word. She has had unusual, even extraordinary, powers her entire life, such as seeing and hearing deities, easily escaping prisons in the CR, and meditating alone without food in a mountain cave for several years. She looks at people and can answer their questions, and the fact that many people find her words and suggestions beneficial was evident by the long line of people streaming in and out of her home. One of her comments to me was that Jason and I could remove obstacles to our happiness and success by hanging two particular types of prayer flags on a high mountain…..What better place than the Drolma-la? Jason and I found it fun and meaningful to leave a rainbow of prayers fluttering in the wind there, and now looking back from Lhasa, it is hard to believe that 800km away, at 5660m, there remains proof we were there, wishing happiness for all beings.

We headed down, past Gauri kund, one of the highest lakes in the world, with that distinctive eerie milky blue green color of glacier melt water. The lake, as you may guess by now, has several stories behind it as well, but offering one of Jason’s photos is probably all I need to say. In the following hour, we lost all the altitude we’d gained in a day and a half, 1800 ft (600m). This is where we saw Tibetans running straight down the steep mountain side, while we looked for switchbacks amongst the stones. At the bottom, a wide river valley opened up, and it was basically flat from here out. We had 4 more hours to go though, and just because it was flat didn’t mean we weren’t tired by the end. We arrived at Dzutrul phuk monastery around 6 pm, exhilarated by the day, but ready to be out of the wind and with a cup of hot tea and water on the kettle for instant noodles. Spending the night at a rural monastery means some time chatting by the wood/dung/trash burning metal stove drinking tea usually until the smoke drives you to a cold room with several beds, suggestion of several mice, and sleeping bag. This night though, another group arrived after dark, and we were asked to give our seats to those coming in from the cold. None of us seemed dismayed by the early bedtime.

Day 3 of the kora:

The single lay religious man who tended the monastery, along with a funny chang (local beer) drinking assistant, gave us a tour (religious visit) of the monastery in the morning. In a cave at the back of the small prayer hall, the hand and head prints of Milarepa were visible. It was here that the Bon master challenged him to a competition of who could build the best shelter; when Milarepa started with the roof, there wasn’t much the Bonpo could say. There was a staff which supposedly belonged to Milarepa (11th c.) which had been damaged and broken in half during the Cultural Revolution. Their valuable collection of very old scriptures and a statue of Milarepa, supposedly constructed from the living likeness of the saint, had survived that time by the bravery of one man who hid them on his property, and returned them in the 1980s. All the monasteries at Kailash were demolished by Red Guards in the 1960s, but the main ones have been at least partially rebuilt, and maintained by a smaller number of practitioners.

We opted to stay together as a group for the four hours leisurely walk out of the mystical valleys and pilgrimage mindset and back into Darchen and the ‘everyday world’. The challenge of pilgrimage to maintain the intentions and outlook generated through the quiet walking and camaraderie once ‘back’ is a significant one. We had some nice conversation, watched some eagles soaring, and marveled at the green, black and blue rocks in the Gold Cliff Red Cliff Canyon. The river valley opened out to the wide plains we drove in on, the saw the Manasarovar lake again, a turquoise strip between us and the towering snow peaks along the national borders. At a pre-arranged site, our driver was offloading our bags from yaks and into the land cruiser. Yakman wasn’t coming into town. We took some photos and said goodbye, and then he asked for a tip. It was that moment of leaving the woods after a weekend hiking and suddenly the transition back hits you with traffic, billboards and noise. Something of the stillness and quiet and lushness of life leaves you just a little bit. We’d been told we’d already paid a good salary for the boy to the ‘leader’, but we learned that was apparently the leader’s cut and the poor yakman hadn’t been paid at all for his time, only his yak’s costs (which we never did figure out since grass is free, but I’m sure we’re just ignorant about the business of yak-ing). We felt deceived by the leader, but also that we didn’t want this kid to suffer for that, so made his three days well worth it. Some said he should use it to buy a watch!

We still had just under an hour to walk the rest of the way back to where we’d started. A few minutes before we reached the outskirts and our guest house, we five linked arms and walked in silence, full of thanks and joy, and then we each offered one word to encapsulate our experience: “breathless,” “intense,” “movement,” “gratitude”.

Back at our rooms in the early afternoon, we washed our hair in hot water basins, changed into clothes we’d left behind, relatively clean, ate some Pringles and drank beer brought from Lhasa. Back at the Om Café for great veggie stir fries, we met a few more of the kind of travelers far western Tibet seems to attract: hard core extreme tourists. Our list includes: 13K John - an English guy who’d driven from UK to Pakistan and on a whim left his car in Islamabad, hitched to Kailash and was doing 13 kora in a row because an Indian man told him it was a good idea to do; Horsehead - without visas or permits planning to ride one horse and walk his second pregnant horse over the mountains to India – does he think they’d just let him back in because he’s British?; Everest - a Canadian who pitched his tent in the coldest windiest spots so he could take photos at 4 am from his sleeping bag; an Israeli woman alone, also without any legal papers to be there; an couple who’d ridden their bikes from Italy and suffered a few too many sunburns in the last six months. Compared to the 15 hour runners and the three week prostrators and the insane Europeans, we look incredibly tame and boring!

Next day of trip, day 8

Driving out of the plains below Kailash and taking in our last views, we passed herds of animals and followed rivers for a while. Then we found ourselves in the utter desert of Guge. Most Americans would compare the landscape to Utah or the S. Dakota Badlands. A huge canyon arose before us, and would be reminiscent of the Grand Canyon but for the range of snow peaks rising above the rim. The vertical exposure of sand and rock and snow was incalculable. It is also hard to explain just how bad this road is. We had to limit the way back seat duty to one hour, and all the women were working the acupressure point near the wrist that soothes nausea. The rough day back in the car was worth it though to see the remains of Tholing and Tsaparang.

This is the Buddhist and art history section, skip ahead for the continuation of our travel story if you wish

The Guge kingdom was founded by sons of the last king of Tibet’s dynastic period, assassinated in the 9th century allegedly for his anti-Buddhist leanings. Tibet broke into many smaller fiefdoms, and wasn’t to be fully unified under a Lhasa leadership again until the Fifth Dalai Lama, in the seventeenth century. But in the 10th c., western Tibet was controlling major sections of the Silk Route trade, and the Guge kingdom was flourishing and supporting a population of 5,000, with thousands more coming for special occasions. Prosperity and power secured, the King Yeshe O determined to restore Buddhism in Tibet, and sent capable scholars to India to gather and translate Buddhist texts. Rinchen Zangpo is most famed among them. He spent many years in India and is credited with building 108 monasteries in the once unified area of today’s western Tibet and NW India (Ladakh, Kashmir, Kinnaur). He is probably the one who told the king of the accomplished and revered Indian Buddhist master and abbot, Atisha, and suggested inviting him to Tibet. The king sent numerous invitations, accompanied by gold offerings, to Atisha which were long refused. An invading army captured Yeshe O and demanded huge amounts of ransom money. It took his nephew some time to gather it, and when ready to turn it over, Yeshe O instead insisted that he was an old man, and the money should be used instead to bring Atisha to Tibet. Atisha may have been moved by this story, but did not reach Tibet before Yeshe O died. Another factor in Atisha’s decision was a dream he had in which he was visited by Drolma/Tara. She told him that going to Tibet would be good for the dharma, but would shorten Atisha’s own life. Atisha packed his bags and headed north along the Sutlej river valley, arriving at Tholing monastery at the base of the mountain atop which is the royal castles. He remained three years teaching at Tholing, which was then a thriving Buddhist center already of 500 monks. He then traveled to central Tibet and taught and composed texts for Tibetans until he dies in 1054, securing the Second Diffusion of Buddhism from India to Tibet. From this time, though Buddhism waned and disappeared in India, Buddhism never again declined in Tibet, until this century that is. It is hard to overestimate the historical and religious importance of this figure, who I’ve heard about since I started studying Buddhism, and thus this place. But Guge kingdom in the early 1600s courteously welcomed the first European visitor, the missionary Antonio Andrade, who obtained permission from the king to build a church. Buddhists in the region feared the king was weak and joined forces with a Ladakhi king to oust the Guge king. Unfortunately, ruling from Leh, or Lhasa, proved too difficult, and combined with the decline of the Silk Route, and perhaps climate change making the area too dry, the kingdom collapsed, never to be re-established. Because the sites of Tholing monastery and Tsaparong, the hill complex of cave homes, temples and castle, had been increasingly neglected since the 17th century, the Red Guards didn’t attack it with the same zeal the summoned during the Cultural Revolution for places of Tibetan passion and active use. Almost all the statues were destroyed, but the walls, and amazing murals, were left largely intact. The dryness and this merciful moment in history means the absolutely superior art of the 15th century wealthy kings commissioned to adorn these temples is still intact. The art here is the bulk of what we have of the “Guge style”, a very particular art, mostly mural painting, of a limited geographic and historical range, best characterized as a synthesis of Kashmiri and Newari (Kathmandu valley artisans, previously influenced by Pala period (9-11th c. NE India) art. The art and architectural influences are so clearly Indian, Nepali and perhaps slightly further West and Central Asian, and so lacking in any Chinese elements at all. The compositions feature singular deities and figures within windows or frames, made by halos and/or thrones, and the spaces between them loosely filled with decorative patterns from the natural world like flowers, leaves and vines. The bodies are long and slender, and adorned with clinging robes or clothes painted with extraordinary attention to detail of fabric textures and patterns – in some chapels with thousands of figures, each one has a unique garment. The colors are brilliant, mostly red or blue backgrounds with haloes and figures in a high contrast color. In the last chapels to be re-painted before the fall of the empire, we can see the beginning of more narrative compositions, with multiple figures in relation to each other, and landscape or scenery filling in the spaces between figures, two major developments which would become common in central Tibetan art after the 18th c.

Our story continues

Tholing is presently run by a few less than brilliant monks who seemed a little put out by having to sell some foreigners tickets and showing them around. One monk escorted us to some chapels and after unlocking a door for us, immediately commenced hurrying us back out again. He also had a drill sergeant’s adherence to the NO PHOTOS rule. After a building or two, he passed us off on another guy (who he summoned from across the courtyard via cellphone), who turned out to be a real gem. We got to chatting and he explained that people in the past who appeared as ignorant tourists took photos which antiques dealers later used to identify pieces of value that would fetch a good price if stolen. After several robberies there, including pieces of painted wooden ceiling planks, they forbade all photos and require doors be kept locked. Never mind pictures of the place are already published in books and probably all over the internet. (This also means only one guy has the key, and when I went back for a second visit, which I’d arranged in advance, the guy with the key had gone for a check up at the town ‘hospital’ and no one could let me back in until hours after we planned to be back on the road.)

This Tibetan man took us into every single chapel, and offered me quite a bit of explanation of how things used to look and what the piles of debris in each one had been. Larger than life size statues were reduced to clay, straw and dust piles; not swept out but crowned with a mostly whole surviving head from a much smaller statue. Collected in a box here and there were recognizable fragments of small statues that belonged on tiny ledges near the ceiling. The roof of one large important chapel, built as a mandala, had been completely destroyed, and the walls were caked with dust and the melting of earthen construction subjected to the elements. A foreign agency had replaced the roofs in the 1990s to prevent further damage, and upon close inspection of spots where the mud had flaked off, murals were still visible underneath. Whether money, international cooperation, art restoration technology, and will can come together to make them again visible is hard to know. I think his love of this place could see that I was moved, and he began urging me, in a whisper, to sneak some photos, then insisted that I feel in my own hands weight of a small statue’s painted heads, detached from their body. Holding devastation in my hands, without the barrier of glass or ropes or rules against photos, was only mitigated by his then holding that and other fragments to the crown of my head, the Tibetan way of receiving a holy object’s blessing. He made Tholing a place that still contained life, some secret lived attachments that could not be museumified.

Tsaparong was perhaps more like visiting a deserted set of intricate ruins anyplace – a young guide, who had graduated from the Tourism Dept. at Tibet University, was the keyholder this time, and the time it took him to recite his memorized English lines about each chapel was about all the time we had inside them. What appeared to us as a dusty, dry abandoned outcrop of stone perched over the Sutlej river valley used to be teeming with activity in three vertical levels. Ordinary people lived in caves at the bottom, monks’ cave cells and brick and wood constructed chapels banded the middle, and the royal summer and winter palaces were at the top, accessible only through tunnels and stairs deep in the mountain. Our guide took us to the famed chapels with similarly preserved murals and destroyed statues, and left us to explore the rest of the ruins on our own. The murals, as I described above, are of spectacular artistry, and I longed for Jason to have proper tripods and lights to document every square inch. I compromised by tagging on for a second tour with a group of military officials from the regional center city who were on their first sight-seeing tour, both to get a second look and to try to snap some images, hoping my camera balanced on the wooden barricades would be steady enough in the dim light. I was really torn between just absorbing what I could by being there in the moment, and knowing I had only a few minutes and might benefit from concentrating instead on strategizing some photos to mull over later. Tough. Photo results disappointing lack of focus, but still powerfully evocative.

We climbed some inner stairs to the summer palace on the ridgetop – getting winded and wondering how we’d climbed much higher only days before. There was only one original building left in good shape, and locked while under the restoration supervision of a Swiss team. But we got the gist of a complex set of storehouses, courtyard performance spaces and audience halls. The winter palace, accessed through a semi-hidden channel from the center of the summer

palace complex, was more perplexing. The tunnels definitely brought out the Indiana Jones in us, as we clung to a loose metal ‘rope’ and tried not to slide all the dark way down! Once we were inside the mountain, we saw the Royal family’s allegedly warmer abode and safety hatch in times of attack and siege. There was even an escape route/ water access tunnel. But, the ‘rooms’ were tiny, low, dark and of bare stone, indistinguishable today from the commoner’s caves far below. We were trying to imagine them full of cushions, candles, tapestries on the wall, etc., but I still can’t say I’d like to have been Royalty there!

From Guge we turned back eastwards to Lhasa. Going over the pass on the way to Darchen, we hit a snow storm. Thinking we were out of it a few hours later, we turned off the main road to spend the night at Chiu Monastery on the banks of lake Manasarovar, hoping for a scenic sunset. Instead, we found ourselves in over a foot of snow and miles away as night was falling. Jeeps and tractors and trucks carrying lots of stuff and people were stuck all around us, and when we got going, we’d inevitably get stuck behind someone spinning their wheels or pulling out a shovel to dig up dirt from under the snow to throw around tires. Thankfully, we had a great driver and powerful 4 Wheel drive, and made it to the base of the monastery and stayed with a wonderful family in their guest house. Again, out of the cold and into a warm kitchen drinking butter tea, we rejoiced in our fortune and hoped the others we’d seen on the road would be turning around and coming in too. The lady of the house cooked us the best yak beef and noodle soup of the entire trip and we slept. The next morning, we were hoping the additional snowfall overnight would reduce the iciness of the road, and in fact we were fine. We were astounded though to see the same folks on truck/bus and tractor not far from where we’d left them the night before, and handed out some biscuits and crackers.

One other jeep, carrying Chinese tourists, got stuck several times in front of us, their 4x4 seemed to have ceased working, or not been switched on. Our driver assisted every time, and Jason and Matt and Christy even pushed once or twice. Hours later when we completely blew, and I mean shredded, a back tire, the driver of that car pulled up out of nowhere full of smiles, happy to return the favors. Change of tire pit time: 15 minutes 43 seconds.

Two long bumpy days in the car later, we arrived in Gyantse, a wonderful town in central Tibet I used to refer to the Wild West town, before I’d really been out west. But in Gyantse, horse drawn carts and people somewhere between town and country are the norm on the streets. The town was probably more modern in the 1930s than today, when it was central to the Tibetan-British Indian trade route, and aristocrats from Tibetan and British society were partying it up together and doing the Charleston. Invaded by Younghusband in 1904 to secure those trade concessions, British determination to make it to Lhasa and exert influence over the coming decades became part of Chinese Communist rhetoric – the PRC was established to overcome and expel foreign imperialists, from the Opium War’s battles in the east coast to Tibet in the West. That is, they still believe Tibetans willingly join and gratefully celebrate their liberation from the British and the theocratic Lhasa government, as you can see in the Anti-British Memorial Museum at the fort. However, today’s main East-West and North-South routes bypass Gyantse, and so, unlike Lhasa and Shigatse, the town’s old buildings haven’t been bulldozed for department stores. Modern consumer goods are available, but fit into the Tibetan character of the town; probably 90% of the buildings are in a well executed traditional architectural style. The jewel of the town though is the 15th c. Kumbum and adjoining monastery. The Kumbum is an immense multistory chorten, one of only two surviving in Tibet in which the pilgrim enters and ascends the floors by processing through dozens of tiny chapels. Again, I was amazed by the 15th c. murals, and Marit and I made good use of the freedom to photograph inside. Our cohort though had seen it, the adjoining monastery and one up on the hill in the same amount of time we took in the Kumbum alone. ‘Seen one 15th c. chapel, seen ‘em all’. As a somewhat historian of Tibetan culture and arts, it was a great learning experience for me though, and rewarding too since I had not visited there since my first time in Tibet 10 years ago.

We had several really good meals back in Lhasa, especially our last night together for a Tibetan feast, chang, and lots of laughs. We almost changed hotels to sleep five to a room without a toilet, just for nostalgia.

Back in Lhasa, Jason and I are more than a little happy to have our room back to ourselves, and though Jason had a nasty cough for a bit, we were just content to be in the same room alone, a luxury we hadn’t had for almost three months. If you are interested in his excellent photographs and version of this trip, and/or his experiences working for three NGOs in six counties in eight weeks, check out his blog at

www.jasonsangster.com/blogSo, we are trying to remember what normal life meant in Lhasa, three months ago, before I went to London, Germany, and Beijing, and Jason to Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. We’ve re-met some friends and research contacts, and settling back in. We should be here until June or July, and you are all most welcome to join us for an adventure any time.

We’re on email and skype a lot, and would love to hear from you.

All best wishes

leigh

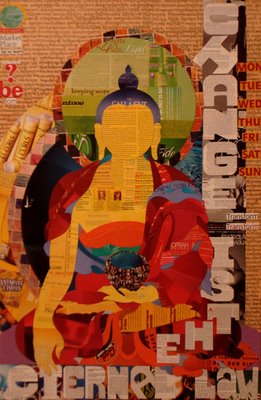

Nyandak’s third work was a project specific piece created in collaboration with Yak Tsetan for the Rossi & Rossi exhibition Contemporary meets Tradition

Nyandak’s third work was a project specific piece created in collaboration with Yak Tsetan for the Rossi & Rossi exhibition Contemporary meets Tradition